By Rebecca Witter and Dana E. Powell [1] §

Structural racism combines with the toxic wastes from industrialized capitalism to haunt the rural lowland landscapes of eastern North Carolina. This territory also hosts the decades-long organizing of environmental justice activists whose analyses of harm, dispossession, recovery, and reclamation reverberate far beyond the region’s sandy soils, pine forests, swamps, and tidal rivers. Our new project is in close conversation with some of these leaders as they redefine rural, anti-racist environmental defense of watersheds, forests, and diverse communities against the contaminating effects of rural capitalism. Core to their labor are strategies for (re)imaging and (re)imagining nature to redress the phantom afterlives of colonialism and enslavement.

This essay offers an assemblage of images: quilts, murals, and photographs of these rural landscapes, captured and co-curated with our collaborators – Jereann King Johnson, Gary Grant, Carla Norwood, Gabe Cumming, and Bill Kearney – and accompanied by preliminary ethnographic insights that they equally inspired. Infrastructures, ecologies, and relationships of violence, of recovery, and of justice, animate these images within and beyond their frames. Compelled by Engagement’s invitation to engage with the spectral politics of rural capitalism, we describe here a few of the ways environmental justice leaders are retelling stories that, visually and materially, defy spectral silences and restore contaminated ecologies. To this work of imaging nature, we bring “ethnography of late industrialism” (Fortun 2012) – modestly, reflexively, and in a manner that enlivens, and might transform, anthropological practices of knowledge co-production.

As white cis-gender, women anthropologists, and children and grandchildren of eastern North Carolina, we have intimate and uneasy connections with our lowland ancestral homes. Witter hails, at least in part, from Kinston, North Carolina, a small city on the banks of the Neuse River. Generations of her maternal kin fill graveyards across Lenoir County, including those dilapidated, and some rehabilitated, on former tobacco land. Witter’s first recollection of Lenoir County, imaged nationally, related to the 1999 Hurricane Floyd-induced floods that displaced hundreds of human residents (on the other side of town) as it drowned thousands of pigs previously confined to industrialized feeding operations and swamped hundreds of thousands of gallons of hog waste. Powell’s lineage is upstream, northwest along the Neuse, on family farms in rural Johnston County. The small town of Smithfield is also known for its pork, including in the form of “red hot” Carolina Packer sausages, and infamous for a singular public image – that of the Ku Klux Klan billboards that loomed large on I-95 and the westside entry to town, welcoming travelers to the “Heart of Klan Country” well into the 1970’s.

These inner coastal plains landscapes shape our memories, our positionalities, and our responsibilities. Yet our lived experiences are fundamentally different from the experiences of those whose stories we have been hearing. The disquieting inheritance of white privilege veiled the phantoms and has shielded us from the contaminating harms of their hauntings. Determined to unearth these specters, and to relearn the past – still fugitive today – we conjure together a few mediums here, with the help and the consent of our collaborators. Note that some of the images are arresting, and those that depict lynchings, imprisonment, and confined animals may be triggering. We share the images with the deep senses of care and respect our collaborators engendered when they introduced them to us.

This essay reawakens origin stories of environmental justice – in response to the siting of a toxic landfill and the growth of industrialized agriculture – by tracing images that activate a (re)new(ed) politics of public memory. Our writing draws from COVID-19-era fieldwork, conducted as safely as possible, in counties across rural eastern North Carolina in October 2020 and in subsequent communications via emails, phone calls, and a virtual university classroom in 2021. Our intent is to show how imaging and re-imaging nature is a vital part of critical activist knowledge in resisting the transformation of homelands into deadening zones of extractivist capital. We have learned that imaging nature is intergenerational and pluricultural work in rural eastern North Carolina. It requires diverse coalitions across the region, renewed recognitions of Indigenous sovereignty and African American land loss and land recovery, and an acute critique of capitalism and contamination.

Origin Story Awakenings

In the late 1970s, the Ward Transformer Company in Raleigh sought to remove 75,000 gallons of oils containing PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) from its used transformer voltage plant. An associate of the company, Robert Burns, stepped in and worked with his sons to illegally dump the toxic oils along 240 miles of rural roadsides across eastern North Carolina (McGurty 1997). Three years later, in 1982, the state permitted construction of a landfill in the small, poor, and predominantly African American community of Afton to dispose of forty thousand cubic yards of the resulting contaminated soils. In response, and following unsuccessful legal measures to prevent the landfill, a multi-racial coalition of regional activists, religious leaders, and local residents (including school-aged children) organized public protests to disrupt the delivery of the contaminated soils. The landfill continued, undeterred, but the protests garnered significant media coverage, establishing public concern for “environmental racism” and lighting the spark that would ignite the environmental justice movement (McGurty 1997; Cole and Foster 2000; Sandler and Pezzullo 2007).

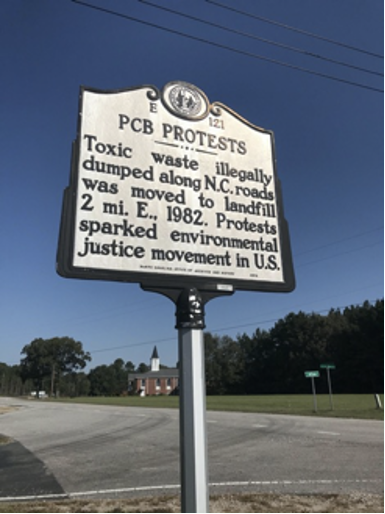

In October 2020, Witter and Powell travelled to see the historic landfill and protest sites and to meet with those working at the intersections between social justice and environmental protection in Warren County today. We learned that aside from the marker imaged below, there is little to designate and to story these events to the public. The events and their social and environmental consequences are not taught in local schools, and typically left un-discussed and uncelebrated, in local discourse.

For the activists who lived it and scholars who teach this history, the public silence on the matter, locally, conjures a ghastly breed of phantom. That contradiction reverberates in the company of other silences. Yet, we will show that quasi-veiled origin stories also invoke, for some, renewed commitments to public history through the imaging of nature and of collective memory.

From Pedestals to Quilts: Textiled Tellings of Fugitive Pasts

In June 2020, the Warren County Board of Commissioners removed the Confederate statue standing sentry in the town’s center – ostensibly, to protect the statue.

The emptied pedestal remains and invites a new public story.

A local monument committee, on which Jereann King Johnson and Rev. Bill Kearney serve, is tasked with re-imagining the evacuated pedestal. Yet, the public is not a self-evident collective (Latour 2005); it is being re-assembled now through the hard work of those who don’t take social alliances for granted.

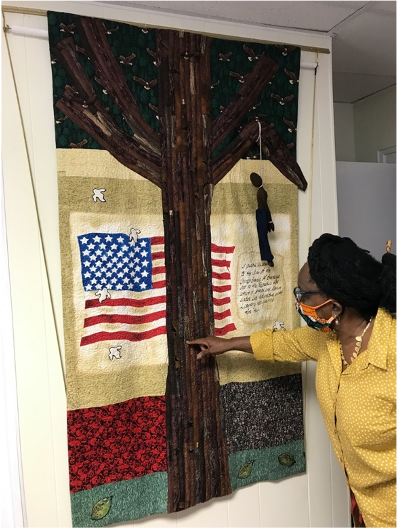

Less than a block away from the spectral pedestal, Johnson and fellow African American heritage quilters counter-narrate and counter-image the recently removed statue through visual re-engagements with colonial and racist violence. Quilts cast from textiles and “seemingly disparate fabrics” adorn the walls and tables of the circa 1870 Hendricks House (home of freeborn Aaron Hendrick and Alice Fain). They offer tactile storyboards – about the loss of Black lands and Black lives as well as about healing, struggle, and survival – that disrupt dominant (White) narratives of this landscape and what occurred there. Johnson began our tour of the Heritage Quilters’ collection reverently, with an arresting black and white quilt created by her colleague in the African American Quilt Circle, Sauda Zahra. Concealed just beneath the dark dye is a faintly discernible U.S. flag, with white block letters sewn atop, “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.”

The quilt replicates signage made by African Americans living in Harlem, New York, during the Jim Crow Era, to publicly denounce lynching events as they were carried out in the southern states.

Zahra’s companion quilt hangs on the other side of the door. Entitled, “American Heritage,” it depicts an actual lynching.

Johnson led us to it, drawing our attention to the small, white ghosts drifting across the flag. The ghosts represent the five states with the most lynchings: Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

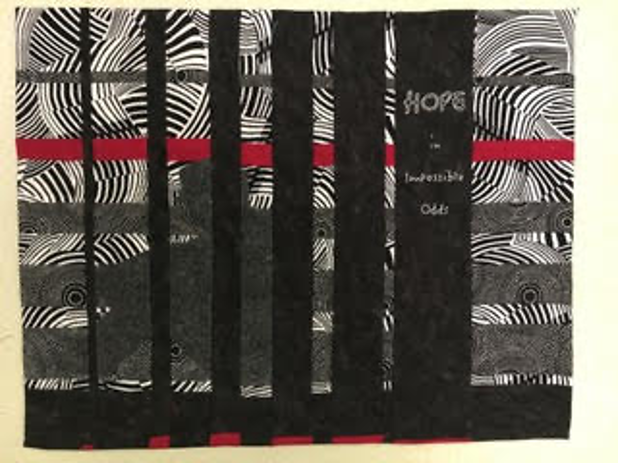

A third quilt made by Johnson, “Hope in Impossible Odds,” depicts a shadowy figure behind bars.

Johnson later relayed that the work struggles with the statistics about Black men and the criminal justice system in the U.S., while also revisiting personal memories. Johnson was born in Georgia then attended college at Howard University in Washington, DC. Growing up, Johnson recalled, how her father and other men could not wear hats, so as to prevent them from the transgression of tipping them in the presence of white women. In “Hope in Impossible Odds,” the incarcerated man, wears a hat, and in this small way, maintains his agency and his dignity.

Johnson taught us how to read the material traces left by crafters in their art, whose edging-work identifies the finished textile as part of the particular style of African American quilt, differentiating it as a genre apart from others. She further explained how the work reveals relations to community and to nature: the cotton fibers Johnson works with her hands connect to ancestors who worked cotton in Georgia, and she noted how trees were used as weapons against African Americans across the region. These are spectral snapshots of environment imaged through encounters with white supremacy in rural southern landscapes. As we saw the visual and felt the textured exchange alive between Johnson and Zahra in these quilts, we also began to hear deeper conversations between collective pasts and their contemporary afterlives.

Murals Re-image Agricultural Legacies

If the 1970s and 80s dumping of PCBs sounded the call for environmental justice in and beyond eastern North Carolina, then the 1980s and ‘90s industrialization of large-scale meat production reverberated that summons. As the sine qua non of industrial animal “farming” technology, the establishment and growth of swine confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) has transformed the region’s ecology, health, and political economy. Led by Smithfield Foods – bought for US$7 billion in 2013 by Hong Kong’s WH Group, in the most expensive transnational agricultural purchase to date – pigs in eastern North Carolina have outnumbered humans for decades. Their numbers are now joined by chickens. When mass produced as food in rural coastal plains, pigs and poultry become unwelcome companions. Take the ongoing, climate change-amplified hurricane-induced flooding of hog waste lagoons, the profoundly negative public health impacts of industrialized animal wastes in predominantly African American communities, and the sheer strength of the pork lobby in state and transnational politics. Aside from when the animals are en route to slaughter, they live hidden behind expansive barn walls in secured campuses (publicly imagined as “farms”). As material specters of rural capitalism, these domesticated mammalian and avian threats to life and to community well-being are most perceptible through their waste.

Two generations of EJ leaders from across the state have taken up the struggle to protect human and environmental health from the contaminating bestowals of industrialized agriculture. Among these, in the 1990s, retired school teacher, historian, and seasoned community organizer, Gary Grant worked with the late activist-epidemiologist Steve Wing and established community organizers, Naeema Muhammed and Nan Freeland, to forge a new critical analysis of racial capitalism’s impact on the eastern North Carolina landscape and its inhabitants (e.g., Wing et al. 2000; Slaten and Scamell 2014). Grant’s analysis included the consequences of modernization and of structurally racist farm loans and subsidies for Black farms and Black farmers (Grant 1999). In 1978 Grant had formed the Concerned Citizens of Tillery in his home community of rural Halifax to counter a School Board decision to close an African American elementary school. By the 1990s, the fight turned to environmental racism, and Grant emerged as a leading public intellectual against Smithfield’s pork power.

We visited Grant, just south of Warren, in Halifax County, at the Tillery History House Museum. The museum stands on former plantation land, worked by generations of enslaved people then by sharecroppers, before becoming part of the New Deal Resettlement Program. The museum tour introduced us to the Grant family, among other founders of the 1935 Tillery Farms, which formed one of the largest Resettlement projects in the U.S. This New Deal federal policy put African American farmers like Matthew Grant, Gary’s father, “back on the land on their own terms,” establishing a secure basis for new forms of sociality and economy to resist the erosion of Black land tenure.

Grant’s tour also introduced us to the work of African American artist, Napoleon Hill, who hails from nearby Northampton County. Hill’s art, like that of Johnson’s and Zahra’s, (re)images nature by asserting and by centering Black experiences – indeed “mapping black ecologies” (Roane and Hosbey 2019) – across the rural South.

An expansive mural marks the exterior of the Tillery History House Museum.

It’s a portal to another time, where the sandy soil, the blue sky, and the pine trees frame the land much like they did on the day we stood with Grant.

Focusing in to the right-side detail, we see a woman hanging colorful family quilts on a clothesline. We recall Johnson’s teaching to “study the edges,” for the material traces of hands past, in the generations long African American quilting tradition.

In the foreground, there is the detail of Matthew Grant, Gary’s father, standing with his mules alongside his acres, planted in cotton.

Views of, and as though standing with, African American farmers invokes an historical ecology of justice and a multi-generational reckoning with stolen land and stolen labor. The image of Gary’s family standing on their farm counter narrates the promises of industrialized agriculture, and primes public imaginings for different possibilities, past and future.

That tour continued back in Warrenton, where just up the road from the Hendricks House, Carla Norwood (Lumbee) and Gabe Cumming cast their interventions into justice and community building. Working Landscapes connects regional farmers and growers with Warren County families, including members of the nearby Haliwa-Saponi Tribe, through their locally-sourced meals program. They involve community youth in learning about local food production, and they help to move the county’s small business sector toward a more regenerative economy.

To scale-up production and distribution, Working Landscapes built a food hub in Warrenton to provide local training and employment and to model an alternative approach to “nature” – as agriculture, as climate, and as renewed responsibilities. The food hub offers this critical analysis and new public memory visually – through their presence and their work on the land and in the town, as well as through murals.

A mural created by Norwood, Cumming, Martha Pentecost, and Jan Burger enlivens the freezer at the food hub. Painted in the early days of the pandemic, it indexes the ethics of care and action that Norwood and Cumming bring to Working Landscapes while visually linking the granular details of their work to their involvement in transnational climate justice movements.

Another mural, by aforementioned artist Napoleon Hill, spans one side of the food hub’s processing building and offers a visual argument in support of eating locally-grown food. The murals underscore that the labor of Working Landscapes is one re-imaging nature, with food and climate justice at the center.

Monuments to Re-member

The meanings and the matterings of the Warren County PCB landfill site persist through this story. We turned to it, on another blue-sky October day, when we met another re-imager of rural Black ecologies, Rev. Bill Kearney. Before Norwood and Cumming introduced us to Kearney, we had followed him from a distance, first acquainted through Pavithra Vasudevan’s short film, “Remembering Kearneytown,” which features the legacy of the PCB protests (Vasudevan 2012).

We stood with Cumming and Kearney – masked and 6-feet apart – outside Coley Springs Baptist Church in Afton. This is the building where community members organized, and prepped those who marched, those who laid down before the trucks carrying the contaminated soils, and those who were imprisoned. Kearney shared his story of the movement on the church grounds, then escorted us to perhaps the most spectral landscape of all: the dump site itself.

Down an unmarked dirt road, overgrown with weeds and flanked by pines, we found the infamous landfill, partially reforested and unceremoniously enclosed by chain link fencing.

The 1982 PCB protests are legendary in environmental justice (EJ) circles. There’s a collection of published literature on the significance of the actions; a global network of environmental justice (EJ) activists sees it “an emblematic struggle” for the world (www.ejatlas.org); and we teach it as such, rather faithfully, to our students. Locally, by comparison, the story of the struggle manifests in a hush. Like the imaged land, it’s flanked and grown over.

As we stood at the landfill site, the affective power of the place was at once epic and mundane. It’s certainly haunted, and not only by the reverberations of local silence, but also by the PCBs potential latent effects. Though the state officially “detoxified” the site in the late 1990’s, Kearney and others in Afton harbor uncertainty about possible linkages between local health concerns and the formerly toxic site. Kearney envisions erecting a permanent marker on the site as a public monument to a struggle that is very much “ongoing today,” given the unresolved questions about health and water, for area residents. Thus, this now internationally-known yet fugitive and ostensibly invisible ruin continues to mark a pivotal turn in collective analytics of the intersections of rural environmental racism, risk, and recovery.

As we prepared to leave the site, a police car approached, ambling down the dirt road toward us then blocking our exit. It was an officer from the county sheriff’s department, coming to see what we were up to. Kearney, wasting no opportunity to educate, gave the sheriff a short lesson on the site, its history, and why two professors from the mountains would bother to come to Afton to see it. The officer, who still seemed perplexed by our interest, allowed us to take a photo with him, but we leave that image for his own retelling.

Public Memory to Expand the EJ Canon

Warren and Halifax County innovators Jereann King Johnson, Gary Grant, Carla Norwood, Gabe Cumming, and Bill Kearney work in tandem to defy forces of collective amnesia and material erasure, breathing new life into legendary struggles through contemporary coordinates of anti-racist economic, ecological, and social vitality. Their critical analyses directly inform this writing, functioning as both compass and companion as we chart and navigate this visualized counter tour. Their work is remarkable, and yet we emphasize that the collective labor and analysis that comprises the revitalization of public memory is underway in counties across rural eastern North Carolina. We’ve shared only a sampling here.

For us, the networked (re)telling of histories and (re)imaging of natures against the stilted phantoms of rural capitalism is all the more revealing as the specters of industrialization persist and mount. They persist in the forms of more landfills sited in African American communities, coal ash dumped in waterways, and pipelines dug in Indigenous territories. They mount as new bioenergy projects – the production of biomass from native forests and biogas from hog and poultry waste – further entrench the powers that be.

In this re-membering of our eastern North Carolina homelands, images of public markers, evacuated pedestals, anti-racist quilts, transcendent murals, and still-to-be imagined EJ monuments entangle and inform the legacies of other collectively remembered vistas, those of KKK billboards and confederate statues, those of arrested protesters and imprisoned men, those of drowned pigs and poultry trucks. The spectral meanings of these images, in and beyond their frames, help us to better sense the stark contradiction between the widespread visibility of Warren County in the EJ literature and the near invisibility of this story locally. As Bill Kearney works to break the silence, other foundational stories stitch their way across this landscape, connecting past and future, and charting other origin stories in need of witness and memorialization in the cannon of Environmental Justice.

Notes

[1] Rebecca Witter and Dana E. Powell shared the authorship of this essay equally. In addition to the collaborators we name and center here, we acknowledge the twenty-two people working in environmental protection and social justice in rural eastern North Carolina whose knowledge, experience, and generous conversations with us also informs this writing. We credit our collaborators for any insights made here and retain responsibility for any faults. We also acknowledge the work and insights of our Spring 2021 undergraduate research assistants, Hazel Pardington, Hannah Bennett, and Edgar Villeda. Funding provided by Appalachian State University’s Chancellor’s Innovation Scholars Award enabled the October 2020 research.

Works Cited

Cole, Luke W. and Sheila Foster. 2000. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Fortun, Kim. 2012. “Ethnography in Late Industrialism.” Cultural Anthropology 27(3): 446-464.

Grant, Gary. 1999. “’Here’s my mule, where’s my forty acres?’: The plight of Black farmers and farmland in Tillery, North Carolina. In Under the Blade: The Conversion of Agricultural Landscapes. Richard K. Olson and Thomas A. Lyson, eds. Pp. 321-327. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McGurty, Eileen. 1997. “From NIMBY to Civil Rights: The Origins of the Environmental Justice Movement,” Environmental History 2: 301-23.

Roane, J. T. and Justin Hosbey. 2019. “Mapping Black Ecologies.” Current Research in Digital History 2: https://crdh.rrchnm.org/essays/v02-05-mapping-black-ecologies/

Sandler, Ronald and Phaedra Pezzullo. 2007. Environmental Justice and Environmentalism: the Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Slaten, Craig and Madeleine Scammell. 2014. “’No Justice, No Peace’ and the right to self-determination: An interview with Gary Grandt and Naeema Muhammed of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network.” New Solutions 24(2): 203-229.

Vasudevan, Pavithra and William J. Kearney. 2012. Remembering Kearneytown. Film. https://vimeo.com/115070233.

Wing, Steve, Dana Cole, and Gary Grant. 2000. “Environmental Injustice in North Carolina’s Hog Industry.” Environmental Health Perspectives (108)3: 225-231.

Rebecca Witter serves as Assistant Professor of Sustainable Development at Appalachian State University. Her research and teaching assesses human-environment relations, environmental meaning making, and the intersections between conservation and capitalism. Recent publications in the Journal of Political Ecology and Conservation and Society examine the more-than-economic meanings of and motivations for illegal wildlife hunting. Her new project (with Powell and other members of the Eastern NC Environmental Justice Co-Lab) focuses on community-based practices and institutions for ‘getting to justice’ amidst contests over sustainable development.

Dana E. Powell is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Appalachian State University where she has directed the undergraduate program in Social Practice and Sustainability since 2012. Her book, Landscapes of Power: Politics of Energy in the Navajo Nation (Duke) traces public debates over energy infrastructure projects as these intersect with concerns over Diné sovereignty and environmental justice. Her current project involves a comparative political ecology of energy transitions in Indigenous territories (US Southwest, eastern North Carolina, and Taiwan). Powell was a Fellow at Cornell University’s Society for the Humanities and is currently a Visiting Associate Professor in the Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures and the Center for International Indigenous Affairs at National Dong Hwa University (Hualien, Taiwan).

This post is part of our thematic series: Imaging Nature.